How Do You Deal With Uncertainty?

What intolerance of uncertainty costs us and why we cling to it

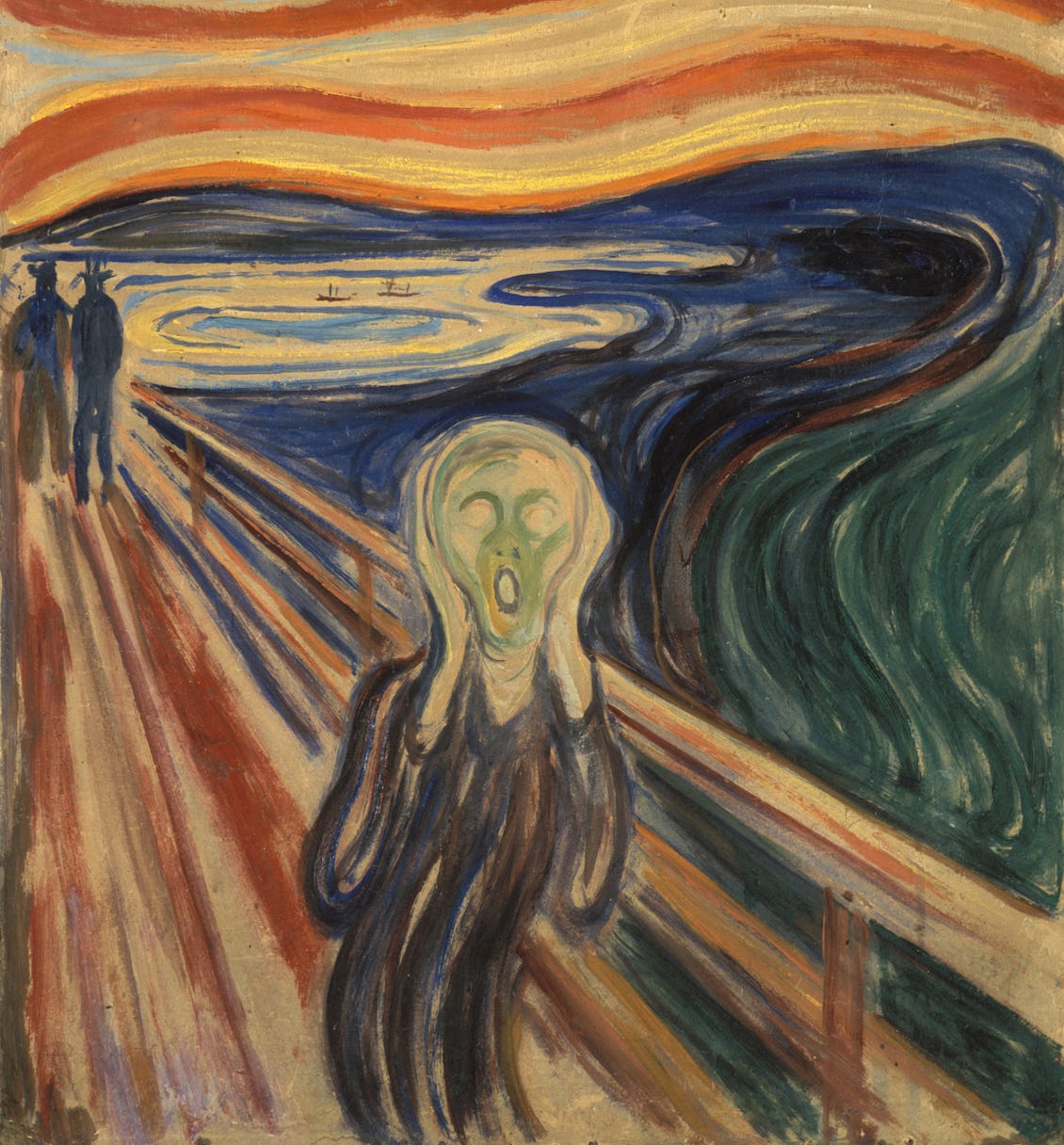

“The oldest and strongest fear is fear of the unknown,” observed American author H. P. Lovecraft, who gleefully exploited it in his horror writing. And although we are repeatedly reminded that our lives are full of things we cannot predict or control – such as weather, politics, the stock market, accidents, illnesses, love interests, or the lottery – we often cling to the deception that says otherwise.

Why we hate uncertainty

A group of researchers at University College London found that people chose guaranteed electric shocks over being uncertain about whether they would be shocked. They reported the most stress when they had a 50% chance of receiving a shock. And their sweating and enlarged pupils confirmed it. So not knowing whether you are going to be hurt feels worse that knowing you definitely will!

Hating uncertainty made sense for our ancestors. When a shrub rustled, some thought, “I don’t know if that’s a lion or just a strong gust of wind. I’ll wait and see.” The others panicked: “Could be a lion - run!” The cautious ones survived and passed on their genes, leaving us with a built-in negativity bias.

While some people are better at going with the flow and not trying to control everything, others (like myself!) are more allergic to uncertainty. They see it as unfair or dangerous, find it distressing, and doubt their ability to cope with it. If you tend to go down the rabbit hole, catastrophizing until you’ve exhausted every bad outcome that might happen when facing uncertainty, you know what I mean.

The price of our uncertainty allergy

Research indeed has found that individuals who are particularly intolerant of uncertainty tend to worry, ruminate, feel anxious an depressed - all of which, in turn, makes them even more intolerant of uncertainty. The uncertainty intolerance is common in most psychological ailments, including Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), OCD, Social Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, PTSD, Major Depressive Disorder, and substance abuse disorders. And it can even make you feel physical pain more intensely and diminish a sense that your life is meaningful.

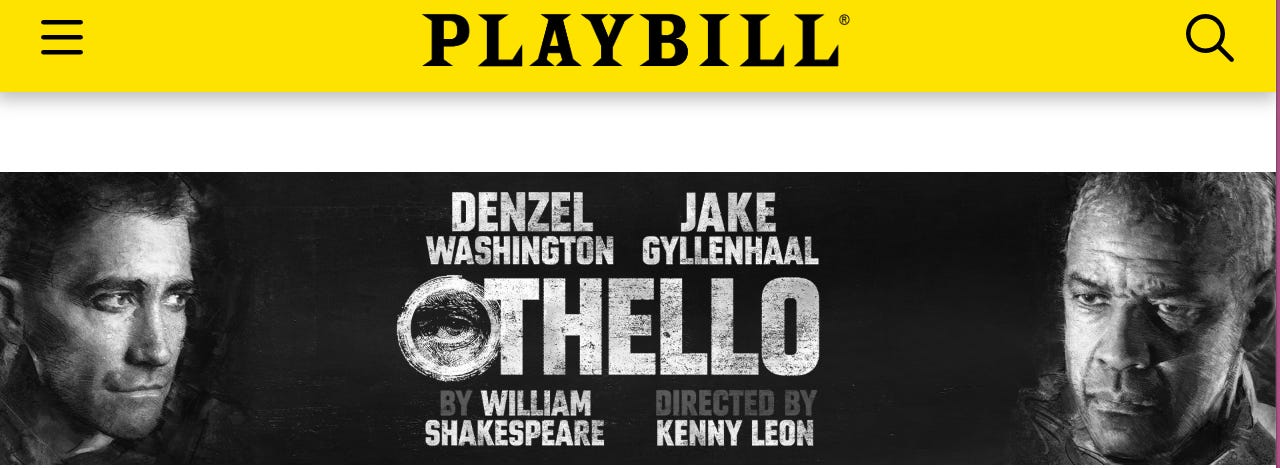

We are endlessly drawn to the downfall born of our own delusions. For example, this year’s Othello on Broadway broke the all-time box office record, showing the enduring power of Shakespeare to illuminate human foibles (although the star power of Denzel Washington and Jake Gyllenhaal didn’t hurt).

Lorenzo Zucca, professor of law and psychology at King’s College London, told me that Shakespeare’s tragedies often show the ruin that follows when we demand certainty at any cost. In Othello, Iago exploits this vulnerability by planting seeds of doubt about Desdemona’s fidelity. “Jealousy is always anxiety about not knowing,” Zucca explained. “If you demand certainty, no proof will ever be enough.”

Othello takes a planted handkerchief as irrefutable proof, rejects Desdemona’s pleas, and kills her - only to realize too late that he was deceived. Overcome, he takes his own life. In his final speech, he admits he loved “not wisely, but too well.” Unable to live with uncertainty, he paid the ultimate price.

In spite of all the negative consequences of fighting uncertainty and rationally knowing that we are not and cannot be in complete control of our future, we desperately hold on to the delusion that certainty is possible. Why?

The allure of a machine-like universe

To escape the distress of not knowing, humans have always chased a sense of solid ground. Religion, rituals, horoscopes, and fortune telling offered explanations and comfort. We’ve invoked gods, ancestors, karma, or fate to explain why things happen.

Science didn’t help. Isaac Newton’s (1643-1727) discoveries at the end of 17th century showed that the physical world was governed by universal, mathematical laws that explained how things moved and how gravitation attracted objects to each other. His and other scientific innovation spurred many to believe nature behaved predictably, just like a machine.

Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749–1827) articulated the idea of determinism a century later. This French mathematician, physicist, and astronomer proposed that, given a perfect knowledge of the present and past, we could predict the future with absolute certainty. Extending determinism to psychology, we might think we should be able to predict a person’s thoughts, feelings, and actions if we had full knowledge of their genetic makeup and everything that has ever happened to them.

Obviously, we are far from being able to know the totality of an individual’s nature (genes) and nurture. But with the speed of technological advances, you might we wondering, “Who knows?” The deterministic worldview has so thoroughly permeated the sciences and public understanding, that we have bought into the idea that we are continuously getting closer to being able to predict the future with certainty. And that our inability to do so now comes solely from our own ignorance - not from any inherent unpredictability or indeterminacy in reality itself.

Even psychologists can’t escape the allure of determinism. When asked whether they believe in determinism in 2024, most of the 368 psychologists and psychology graduate students surveyed basically said, “We’re not sure,” with the younger ones more likely to endorse the belief.

Laplace’s deterministic universe began to unravel in the 20th century. Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle showed we can’t know both a particle’s position and momentum, opening the door to quantum mechanics. Science revealed randomness as a fundamental feature of reality and whole systems behaving in ways irreducible to their parts. At best, our predictions are probabilistic - computers and AI may refine the odds, but certainty is impossible.

Despite the cracks in the machine view of the world, we remain drawn to determinism’s seductive promise: comfort in the belief that beneath life’s chaos lies a structured, discoverable pattern. But that vision blinds us to reality and corrodes our mental health.

Determinism is only one culprit in our enduring delusion that certainty is possible or even desirable. I’ll explore others, and how to ease our “uncertainty allergy,” in future posts. For now, I invite you to think about your own approach to uncertainty and how well it serves you.

To reflect on

Where does intolerance of uncertainty show up in your life?

How do you usually respond to it? How well does that response work?

If we knew someone’s genes and every life experience, could we predict their thoughts, feelings, and actions?

Love these insights! I used the same rustling in the grass example in my last novel! (My protagonist Mia was allergic to uncertainty for sure. That was her main weakness and her arc was all about that!)

All human babies are born with two instinctive reflexes - fear of falling, and of loud noises (the "flinch" or startle response) which seem to be built into our biological hardware as survival mechanisms. All other fears are acquired through our experiences and interactions with the world. We are all born into families, some more functional than others, with parents more mature and better adjusted and emotionally capable than others of providing nurturing and safe homes. We all live in cultures and societies with their evolved expected responses - e.g. to human or divine hierarchies, to be cautious in crossing a road with traffic, to fear corporal punishment or public shaming as a child in authoritarian schools or rigid disciplinarian families which believe in not "sparing the rod." Children who grow up that way or are deprived of a home as a place of comfort and safety, a source of emotional closeness, sustenance, and strength, can grow up more fearful of what could happen in life - which is, by definition, unknown and uncertain.

Some babies are born with a hypothalamus programmed for a hypersensitive "setting" before birth, which can have lasting effects on the stress response. That "setting" is influenced by both genetic factors and the prenatal environment of the baby (e.g. the stresses on the mother during pregnancy). This is a complex process with multiple mechanisms in which the key factor is the HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis, a central part of the stress response system. Epigenetic changes (e.g. because of prenatal stress on the mother, who could be malnourished or suffering emotional traumas such as continued grieving for deaths of previous babies) can lead to methylation of genes related to the HPA axis and elevated levels of glucocorticoids. Prolonged exposure to these hormones of the fetus can impair the negative feedback loop of the HPA axis causing it to produce a heightened stress response throughout life. Early life adversity, such as the mother's stress during pregnancy, can reduce the sensitivity of glucocorticoid receptors in the hippocampus, leading to a prolonged stress response in the infant. Maternal stress is also associated with structural changes in the limbic system, including an enlarged amygdala, which enhances the stress response.

All of this is to say that we do have certain emotional capacities and strengths which vary in terms of being able to tolerate and deal effectively with the stress created by uncertainty. If for a hypersensitive child, the expectations of parents and their reactions are uncertain and can be threatening or humiliating and hurtful for reasons the child can't understand or manage, such a person later in life would find it more difficult to tolerate uncertainty. The apparent protection of a god or saint, appropriately invoked, with the right rituals and prayers, could alleviate the anxiety for a time, but it would be provoked again by the next unexpected jolt. What may work better is to work towards greater emotional security, whether that is through meditation and stress management through exercise and breathing deeply, or with professional psychological help, and hopefully in one or more close relationships of trust, even if those were not possible earlier in life.

As for determinism as an encompassing explanation, that's evidently not true in quantum physics - the underlying basis of physical reality, or for that matter in life, in both of which randomness is present. While genes and life experiences can make some outcomes more likely than others, there's no unalterable end-point knowable in advance. That seems to be a plausible conclusion from the longest-running study of any single group through life, the famous Harvard Study of Adult Development. See the link:

https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2017/04/over-nearly-80-years-harvard-study-has-been-showing-how-to-live-a-healthy-and-happy-life/